Intermittent fasting: a human biochemistry perspective

A third article that focuses on understanding intermittent fasting from the perspectives of hormone chemistry and biochemistry.

This article jumps into inspecting some hormone chemistry in order to support our science-backed theory that intermittent fasting is a healthy thing to include in your lifestyle and is also an optimal meal frequency strategy for what should be everybodies goal: to build lean body mass (muscle) while holding fat mass constant, or reducing it. The purpose of this post isn’t to argue as to why this should be everyone’s goal, but we will briefly address it here in case anyone is hyper-fixating on the “reduce fat” part of the previous sentence.

We suggest that you read our two other prerequisite articles first in order to warm up for this one, as this one is the heaviest so far terminology-wise, and will be easier to understand intuitively if the previous two have been read. Furthermore, we make a few connections with those articles.

A simple evolutionary argument:

A simple physics-based argument:

To begin, I think it’s worth discussing the main effect those that fast intermittently feel, and that is a boost to their alertness. There are many reasons for this, which are aided by a ton of scientific evidence that shows that alertness and cognition are improved while in a fasted state compared to being in a post-meal state. The two largest factors for this are in my opinion, primarily a larger availability of blood for the brain (because the digestive organs are resting and do not require much blood flow compared to if they were in the process of breaking down food), and secondarily a boost to resting adrenaline and noradrenaline levels in the bloodstream.

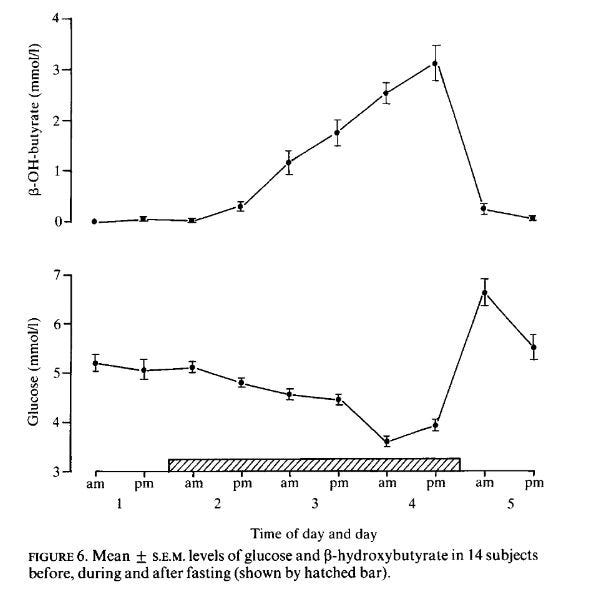

First and foremost, it’s worth taking a cursory glance at a plot of ketones (beta-hydroxy-butyrate) and glucose, as well as a plot for insulin. To ensure that blood sugar isn’t dropping too low, and if it is, that ketones are increasing by enough to maintain mental clarity. There’s ample literature on how lowering meal frequency, and specifically doing so through intermittent fasting prevents diabetes, and there’s even literature that a five-day fast in people who are pre-diabetic has the potential to reverse the pre-diabetic state. Jumping into this, we will inspect a series of plots from some research in the Journal of Endocrinology (endocrinology is hormone chemistry)

Figure on glucose and ketones. At the bottom of the figure is a rectangle with diagonal slashes. These slashes correspond to when the fast was performed, starting at 12 am the night before. This clearly shows that blood glucose barely changes over the first 24 hours of fasting, and hasn’t even decreased by that much after 36 hours of fasting. On a concentration basis, ketones in the blood are increasing faster than the concentration of glucose in the blood is decreasing.

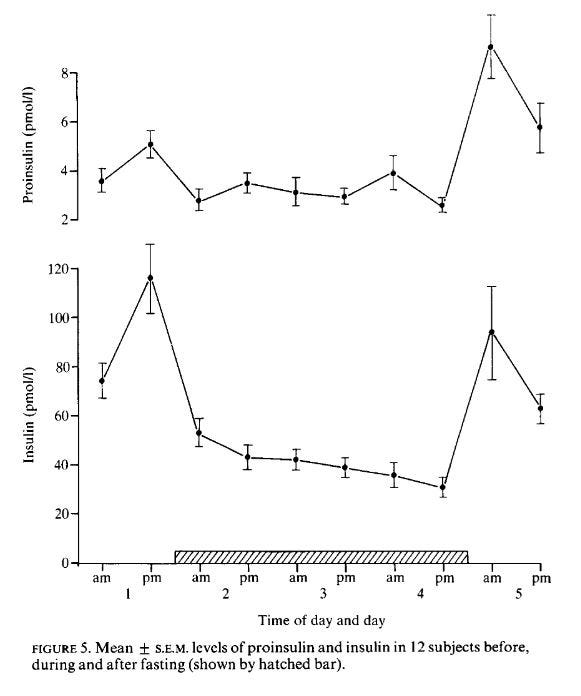

Now, a plot of insulin:

Figure on insulin: We see that insulin is substantially lower than baseline insulin on non-fasted days. This totally supports the hypothesis that intermittent fasting prevents type 2 diabetes. Even just twelve hours after the fast has begun there is a substantial drop in circulating insulin levels, such a drop provides two benefits. The first is that the insulin sensitivity of our cells will increase — our cells will upregulate insulin receptors in order to get more sugar transported into them. The second is that our pancreas quite literally gets a break, and a chance to repair itself and reduce any inflammation that may be occurring inside it.

It’s reasonable to conclude by these plots that there shouldn’t be a reduction in mental clarity or cognition due to a loss in blood sugar, because this research in healthy people showed that blood sugar barely decreases over the first 24 hours, and what it does decrease by is compensated for by an increase in ketones (which are used by the brain for energy). Moving on, let’s inspect the boost to adrenaline and noradrenaline that is provided by intermittent fasting:

Figure on adrenaline, noradrenaline, and dopamine: Subjects in the study had their last meal the day before, and the fast officially began at midnight. We can see that upon waking, their noradrenaline and adrenaline levels undergo a substantial increase compared to where they were the previous day, which was a well-fed state, and the final day, which is again a well-fed state. See Beer et. al. for the paper.

Off this information alone, we can conjecture that fasting would assist with weight-loss more than calorie restriction as the presence of adrenaline and noradrenaline in the blood will correspond to an increase in metabolic rate. Indeed, many studies support this, with intermittent fasting being found to cause more fat-mass loss compared to caloric restriction e.g. this one or this other one.

Another interesting phenomenon in the literature, however, is that almost all the studies that have posed questionnaires to people undergoing caloric restriction in order to lose weight have concluded that caloric restriction “causes” negative impairments to thinking, learning, and cognition in general. These studies are remarkable in that they are for the most part concentrated on young adults, and never used any tests — they just asked questions. They are strongly refuted by the existence of studies that measured changes in cognition quantifiably with tests, and these studies have all found this wasn’t the case. In fact, studies that use measurements report the opposite — that it’s the case that caloric restriction results in a boost to cognitive capabilities.

A natural question to ask then, is whether caloric restriction is better than fasting for boosting cognition. The answer in this study is a clear no because both fasting and caloric restriction were found to boost cognitive capabilities! They both boosted it by about the same amount too — there was no significant difference between the two groups. It’s worth noting that some studies on Muslims undergoing Ramadan have found that the type of fasting undergone during Ramadan, without water, without food, and with waking up during the night to eat, can impair cognitive abilities. In my opinion, this makes sense as both dehydration as well as disruptions in sleep will contribute to impaired cognition. As a result, I choose to exclude them from my world model of intermittent fasting because it’s fine to drink water, and even black coffee or plain tea, aka stay hydrated, and it’s also not affecting sleep quality.

Heading back to biochemistry for a moment, we will inspect how fasting affects human growth hormone (HGH) levels in the blood by looking at a plot, as research has consistently found that HGH is increased by fasting, e.g. see this paper, or the one the plot below came from.

Figure on HGH: We see marked increases, especially in men, in human growth hormone levels in the blood growing rapidly at the start of the fast, and then growing slower after about 16 hours. If I had to guess, this plot is probably one of the main reasons why the 16 hours fasting, 8 hours eating style of intermittent fasting was proposed because HGH is widely misunderstood and thought to provide benefits that it doesn’t provide. Trivia: it’s called human growth hormone because it helps children grow taller. What it doesn’t do, is make muscles grow.

So we see that HGH levels go up a substantial amount for men, as well as women. HGH is the hormone that helps repair connective tissue, tendons, and ligaments, and also shifts the human body towards a more fatty acid-based metabolism, i.e. it encourages the breakdown of fatty acids for energy instead of carbohydrates and amino acids. This is important because it means fasting helps heal injuries, and also helps to further explain the additional loss in fat mass as well as provides biochemical evidence supporting the ability to gain lean muscle while engaging with slight caloric restriction and fasting simultaneously. The reason is that due to the promotion of fatty acid usage while fasting, more carbohydrates will be available for energy whenever it is needed, and thus the overall usage of amino acids for energy should be lower, which means more muscle-protective effects (since the body is less likely to break down muscle). It’s extremely important to mention that while HGH quite literally contains the word “growth” in its name, it does not help you grow large muscles, and in fact, it slightly impairs workouts if it is present in the blood at too high concentrations. These would be the concentrations that bodybuilders that inject HGH would have. The reason it impairs workouts is exactly what is discussed above — by shifting the body’s metabolism to a preference for breaking down fatty acids, energy is harder to get quickly. Fasting will not push HGH high enough to have a large effect on this. There’s actually a lot of research arguing that fasted workouts are better (though I personally don’t engage with this because of our previous article highlighting the importance of protein before a workout, linked below).

Making a connection with our evolutionary argument, we see that HGH levels rise (and shift the body towards using fat for energy), and this is what using evolution as a model would predict — some changes will occur such that fat is used more for energy when food is scarce to preserve protein and carbohydrate. Furthermore, we saw that THE catecholamines (dopamine, adrenaline, noradrenaline) are all increased significantly by fasting, and this also makes sense. The catecholamines are hormones made by the adrenal glands (two small glands above the kidneys). These hormones are released into the body in response to physical or emotional stress. If you’ve heard of epinephrine (medically used in EpiPens for injection into people suffering anaphylactic shock), this is essentially another name for adrenaline. The catecholamines have a performance-enhancing effect, both mentally, and physically, and it’s sensical that it would increase to help the now-starving human with hunting its next meal.

So to conclude, intermittent fasting increases metabolic rate via the release of catecholamines (adrenaline), improves insulin sensitivity and provides our pancreas with a much-needed break (especially if we were previously eating 5 or 6 meals in a day), helps injured soft tissue and connective tissues heal (via HGH), and allows for a calorie-restricted diet to be muscle protective (via HGH). This, put together with our previous article on variety in nutrition, we are starting to build a theory of metamodern health.

Best wishes to all readers,

G

The citation at the core of this article:

Beer, S. F., et al. "The effect of a 72-h fast on plasma levels of pituitary, adrenal, thyroid, pancreatic and gastrointestinal hormones in healthy men and women." Journal of Endocrinology 120.2 (1989): 337-350.